Of The Digger, the counter-culture, and Helen Garner

In 1965 I was a med student at Monash and over the summer holiday a couple of mates and I launched a pop music newspaper called GoSet. It was a full-colour tabloid that inside three years was selling over 70,000 a week Australia-wide. I spun off a pop colour mag in 1968 and in ‘69, a more grown-up tabloid of news and reviews of rock music, theatre, film, and the global youth uprising, immodestly titled Revolution. I launched the Australian edition of Rolling Stone in ’71 and in ’72 a more serious fortnightly broadsheet newspaper by and for Australia’s unfolding counter-culture, called The Digger. By then I was 26.

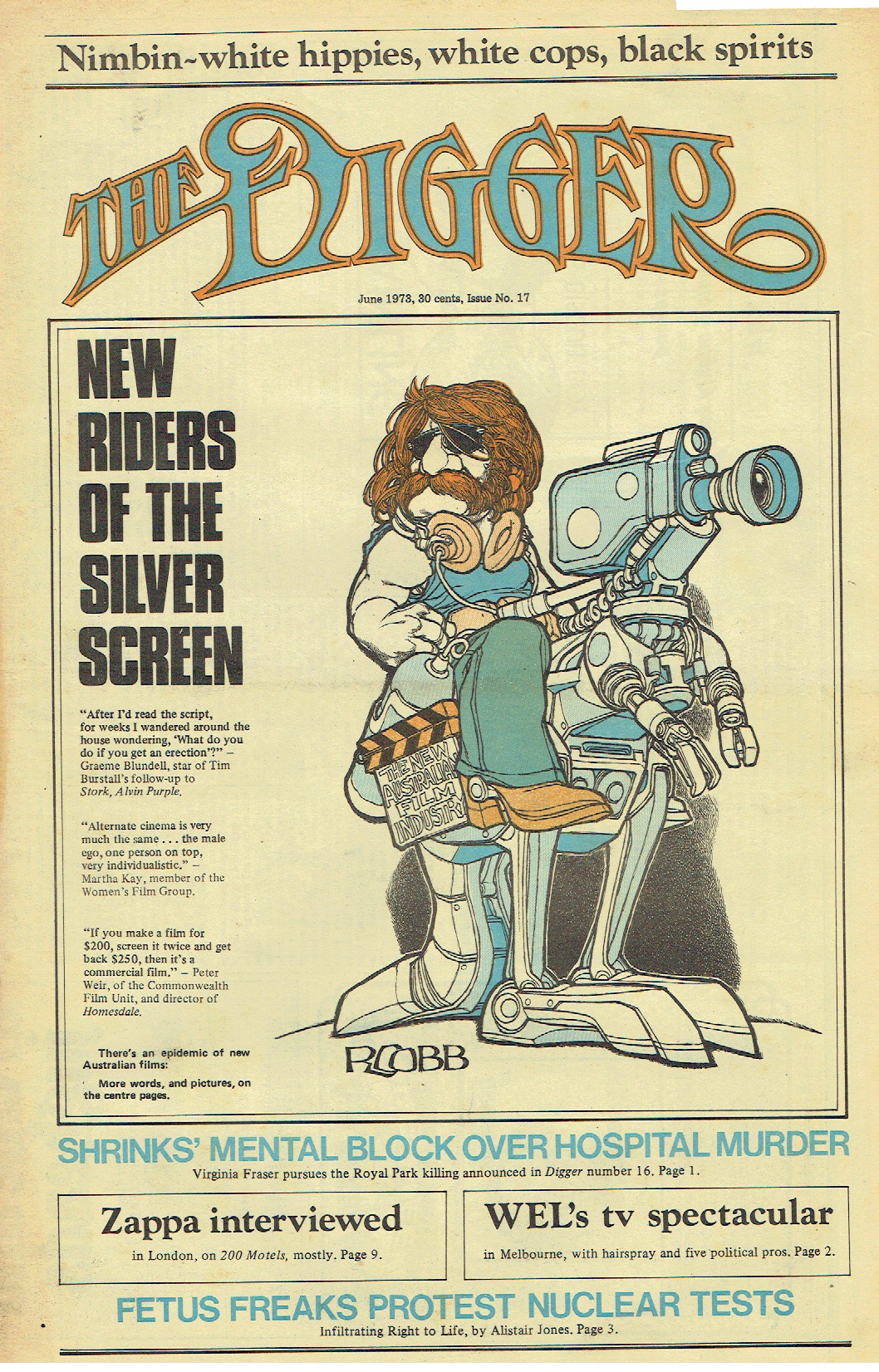

A 1973 cover page of The Digger, the magazine in which Helen Garner made her (fateful) reporting debut

What was all this frenzied publishing and editing about? Like with social media today, new technologies bred new cultures: the new tech of the ‘60s was electrified music, photography-based printing, transistors, TV, and the biggest culture changer of all, reliable contraception known as The Pill. But unlike social media, the counter-culture arose with a purpose: it demanded social changes — which I considered urgent and undeniable — and that was what all these papers were about. The Digger took on culture change as its mission: it brought together writers, thinkers, artists, and activists, all eager to take over the dying cultures we’d inherited and redefine them.

1972 was quite a year. While I was planning my new newspaper, Germaine Greer came home to Sydney to launch The Female Eunuch, and we shared a house in Paddington as a base for our respective projects, swapping gossip and ideas in the kitchen, on the run. I had never met anyone with the knowledge, originality, and the mental and physical energy this woman had, and I resolved that The Digger would at least adopt her spirit.

A week after she left, an American journalist named Bruce Hanford came to talk. He’d flown to Australia instead of going along with the US military on their mission to kill people in Vietnam, and had found work as a journalist on Rupert Murdoch’s Melbourne tabloid misnamed Truth. He told me The Digger’s biggest challenge would be to find good writers, by which he meant investigative types, or original analysts, and I agreed, so I contacted the author of two well-written articles for Revolution. She was a high school teacher by the name of Helen Garner, and we met for the first time over a Jamaican dinner in Carlton the week of Digger’s first issue. She was easygoing, and direct. “Why did you print that stupid story about Daddy Cool’s drummer and groupies?” she asked before we’d finished the soup. “On the cover of the first issue?”

“I think we were scared no one would buy a paper about alternatives,” I ventured, knowing this was an indefensible position, “so we pitched the cover to rock music fans.”

“It was awful,” she said, “and no one except teenage wankers would have read it”. That noted, she said she wanted to write about real life and to cut the crap in content and style, and I said that was what Digger would do. I also gathered that she had split from her husband and had no live-in lovers. I didn’t either, and as our community did back then, we wasted no time becoming involved in each other’s lives.

By October, Digger had published five issues of good stories — on abortion, drugs, Aboriginal rights, pornography, AFL footy, Pine Gap, country music, theatre, and Einstein. Helen and I were in love with each other and several other people each, and when she had a free weekend, she came to stay at the Paddington house, now home for me and my friends and co-conspirators Jon and Ponch Hawkes.

We all talked, shared innumerable joints, ate healthy food and Fruitos, and listened to Maybelle Carter’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken. Ponch had been struggling to get the mostly male Diggers to focus on feminist issues and was thrilled that Helen was now inside our circle. Much of the weekend talk was about love and sex, and unraveling the ties and lies that bind us on both fronts – but then Helen had to catch a plane home to teach at Fitzroy High School.

A few days later I was back in Digger’s South Melbourne house, reading a story I found on my desk – Helen’s first submission to The Digger. The opening paragraph told me that her by-line would have to be “Anonymous”, and that tumultuous days lay ahead. I couldn’t wait.

“One afternoon last week my form one kids and I were about to [study] Ancient Greece,” it begins, then explains that each kid has a book with photos of marble statues of women and men, some of them naked. Naughty students from previous classes have drawn outrageous defacements on the images, such as “a monstrous cock … with a colossal stream of sperm hitting the bull’s eye, the cunt of a woman on the facing page who is modestly demonstrating the folds of the Ionian chiton.” So Helen is now facing 29 excited girls and boys aged 12-13, and her uncontrollable response is to laugh, and immediately all these kids, mostly from poor families recently migrated from Mediterranean countries, are laughing too – until Helen holds up a hand and says, “Look, the reason why people do these drawings and we laugh at them, is that sex is more interesting than just about anything else, and most kids at school don't know nearly as much about it as they need to. Do you want to talk about it?” They sure did.

She describes herself answering all their questions, after telling them to call things by their common names. She has the shocked attention of every one of her students like never before, and, I figured, of every Digger reader too.

The first question Helen plucks from the pile of paper on her desk reads “Why does the women have all the pain Miss?” I made that the headline of the story and ran it on page 3, signifying it as important, but not news like the fact that touring British rocker Joe Cocker was being deported by the Liberal government for pot possession (thus helping Gough Whitlam’s Labor Party win the elections a month later, ending 23 years of conservative rule – like I said, ’72 was quite a year).

Only one Digger reader sent a critical letter, which pointed out that the anonymous teacher had not mentioned homosexuality. Two readers who were more outraged were the Fitzroy High School caretakers, a couple named Mr and Mrs Lack, who somehow discovered that this class was in their school – and they let the cat out of the bag, and Helen was anonymous no more. Melbourne daily papers and talk radio went nuts and she was suspended by the Department of Education. The progressive Victorian Secondary Teachers Association went on strike in support of this teacher who’d told her class that yes, she had sucked a cock… but the bureaucrats had their way and Helen Garner was now a household name, but an unemployed one.

So we asked Hels to join the Digger editorial collective, at our standard rate of $40 a week, and, informed by Bruce Hanford’s two-hour course on how to be an investigative reporter, she wrote excellent pieces on corrupt union bosses, dysfunctional welfare systems, and showing up at the gates of the US satellite spy station at Carnarvon in Western Australia. She also wrote some ripping reviews, such as the one about the new film that had set a ticket-sales record for an Aussie production, headlined “Alvin Purple is a crock of shit”. She co-wrote, with Alan Robertson of the Pram Factory theatre, a piece on the virtues of bicycle riding. That’s them pictured on the cover with her daughter Alice.

Helen remained a Digger writer and editor until 1975, the year the magazine ran out of money and lawyers. Then she began writing books for a living, not infrequently adapting material from her handwritten diaries, which she had long stashed under her mattress aware that friends (including me) took a peek.

Our personal relationship had been built on shaky ground, she being a parent and me being resolved not to be one — and proclaiming that my primary commitment was to radical publishing. Early on, when this shakiness was first confronted, she wrote me that “I’m afraid that my enforced immobility … will turn me, in your mind, into a welcoming and undemanding sort of SPRO [espresso] BAR cum POOL HALL, open 24-hour a day and obligingly functioning on demand, standing idle whilst the customers dally elsewhere, and called into service when alternate amusements pall. Well,” she had the generosity to add, “that image got a bit out of hand!”

I had already understood that the counter-culture included feminism, lecturing Richard Neville in an issue of Revolution a year before that women, comprising half the world, are “the biggest sleeping giant of all”. Of course, making that declaration was nowhere near so hard as living with it proved to be.

Our relationship broke down painfully, but we continued writing each other letters in ink or on typewriters, from Fitzroy to Glebe, or later Paris to New York, about editing magazines and writing novels, gossiping and arguing about love, gender, power, privilege, children, care, trust, dishwashing, and forgiveness.

Helen has said that she strives to be “dispassionate” in her writing, but when the kids in form 1B were desperate to know and understand, she delivered revelation and explanation with passion, in the hope of elucidating, or even resolving things that seem unsolvable. She has continued to reveal and explain, with a passion that sometimes obscured how it affects those being examined in print. How far ahead did she think about how those kids in Fitzroy in 1972 would be affected by that lesson on Greek sculpture?

In a recent article in the Guardian Tegan Bennett Daylight laments that her tertiary-level students are “offended” by Garner’s novel Monkey Grip. They find it “too sexually explicit, too full of ‘profanity’” and the lifestyle in the Falconer St group house is too foreign for them to relate to.

In a recent email Helen recounted that, at a book reading the previous month, she saw three middle aged women approaching and recognized them as long-ago members of form 1B. After hugs and tears of joy all round, one of the women introduced her tall teenaged daughter, who was proudly holding a copy of Monkey Grip.

A few days before the ‘scandal’ of her 1972 lesson broke, she sent a letter in which she wondered “would they sack me if the story got out?”, then reassured herself that the kids “wanted to know the truth.” She gave them the truth the same way she always has: by scraping the rust and mold from our culture to reveal its true shape, hoping that might point to new solutions. Just as The Digger set out to do 45 years ago.

[A shorter version of this article was previously posted here. This version was posted at dailyreview.com.au on 7 January 2018.]

___________________________________

The full text of Garner's Digger article from November 1972 is the next post (chronologically) on this blog, or in issue 6 of The Digger at http://ro.uow.edu.au/digger/6/, or in her 2010 book True Stories.